Housing and Community Health: An Interview with Dr. Paul Dworkin

Nov 12, 2024

This is the first in CHFA's new interview series, "Housing and...", exploring how housing connects with and influences various aspects of our communities, such as health, education, economic opportunity, and beyond. Each installment will feature insights from thought leaders and practitioners in their respective fields, helping to highlight the critical role housing plays in shaping broader societal outcomes.

In this inaugural interview, Dr. Paul Dworkin shares insights from his decades-long career in pediatric and community health, highlighting how stable housing serves as a foundation for well-being and health resilience. This conversation illustrates how interconnected services—from healthcare to community resources—can foster healthier, more stable communities.

Dr. Dworkin serves as Executive Vice President for Community Child Health at Connecticut Children’s Office for Community Child Health and is the Founding Director of the Help Me Grow National Center. He is also professor emeritus of pediatrics at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine. For 15 years, Dr. Dworkin previously served as physician-in-chief at Connecticut Children’s and chair of pediatrics at UCONN.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marcus Smith: You’ve had an impressive career focused on pediatric and community child health. Could you share how your own journey led you to recognize the importance of housing in shaping a child’s health and well-being? Was there a specific moment or experience that brought this issue to the forefront for you?

Paul Dworkin: I’ve usually characterized my career as the relentless pursuit of an answer to the question, “How do we best strengthen child health services to promote children’s optimal health, development, and well-being?” This was a logical starting point for me as a pediatrician, and my colleagues were primarily pediatricians too. This goes back many decades.

Then in the 1990s, we recognized that we needed to expand beyond focusing only on child health services and toward other sectors also crucial to promoting optimal health, development, and well-being: early care and education, like Head Start and childcare, and family support. That shift informed our efforts around the Help Me Grow initiative—a comprehensive, integrated approach to developmental promotion, early detection, and referral and linkage.

With the new millennium, we began to understand more about “the biology of adversity,” which encompasses adverse childhood experiences, toxic stress, and social drivers of health. This brought a new appreciation for the overwhelming impact of social, environmental, behavioral, and epigenetic drivers of health and development, like housing. The question became, “How do we best strengthen families and communities to promote children’s optimal health, development, and well-being?” This shift is significant. It’s what drives programs like Healthy Homes.

MS: You’ve been a strong advocate for an “all sectors in” approach to addressing community health challenges. Could you explain what this approach entails, and how you see housing professionals playing a crucial role in improving child and community health?

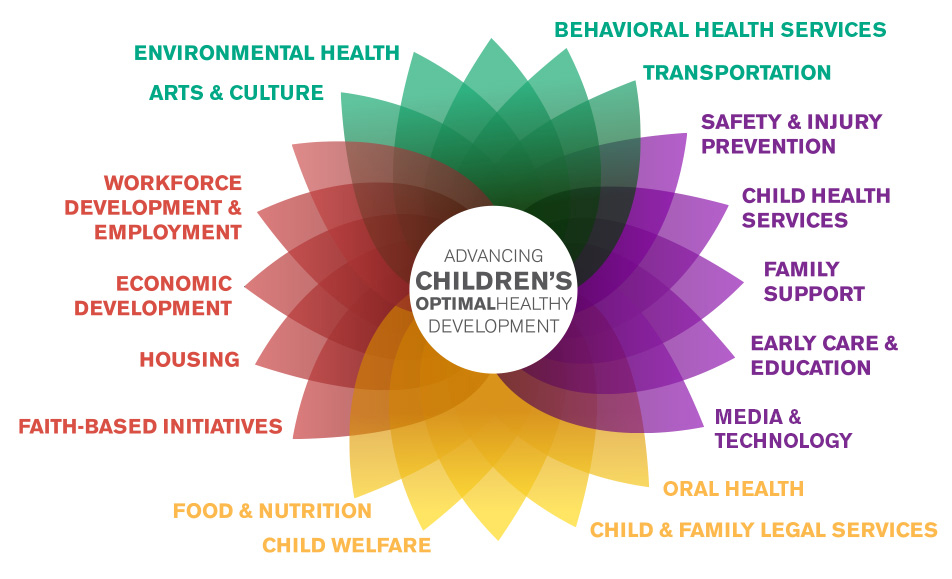

PD: “All sectors in” may seem obvious, but it’s challenging to operationalize this concept. The minute you mention “system building” people’s eyes glaze over. To make the concept more accessible, we use a flower diagram with each petal representing a sector vital to the system. These sectors strengthen families and communities. The latest addition is environmental health, and we’re discussing adding technology as a new petal for its role in informing and mobilizing communities.

Courtesy: Connecticut Children's Office for Community Child Health

MS: That’s a great way to visualize it. It’s about meeting families where they are and starting with their priorities, right?

PD: Exactly. Often, families mention stable and secure housing as a primary concern, which allows us to address these issues directly through referral and linkage. Building a system that supports this has major implications for well-being. One key message we emphasize is that health is not an end in itself; it’s a means to an end, with well-being being the ultimate goal.

With housing, we understand that instability and insecurity can compound with other adverse factors, and issues like insufficiency, weatherization, and safety become intertwined. Housing instability can also have broader impacts, such as on the elderly, who often support younger family members in multi-generational households. This compounding effect is also visible in how frequent moves contribute to chronic absenteeism, affecting school performance. Another example is the lack of housing instability and frequent moves, and that certainly contributes to the devastating impact of chronic absenteeism and school performance.

MS: Frameworks like the Social Determinants of Health have shaped our understanding of the connections between housing and health. How have these frameworks evolved in recent years, and what emerging ideas or shifts should professionals in cross-sector work—like housing and healthcare—be paying attention to?

PD: It’s still very much about “Social Determinants of Health,” though there’s been a subtle shift toward describing these as “social drivers of health.” This shift helps us view health not as an isolated outcome but alongside well-being, which includes factors like joy, hope, and happiness. One significant shift has also been in how we view health services’ role. They only account for 10–20% of overall health outcomes, with 80–90% driven by social, environmental, behavioral, and epigenetic factors. For example, our current target population for early detection and intervention has expanded beyond children with clinical diagnoses to include vulnerable children at increased risk due to social, environmental, and behavioral factors. The CDC estimates that this broader group makes up 30–40% of all children, with even higher numbers among underserved populations.

MS: So, it’s really about rethinking who we serve and understanding health in a more comprehensive way.

PD: Exactly. This evolving view means we need cross-sector collaboration, including child health providers, early education, childcare providers, and family support services. Yet, when research examines the interface between these sectors, it’s often virtually non-existent. Strengthening these interfaces is a huge opportunity—what we call “low-hanging fruit”—and it’s foundational to our approach in system building.

MS: As we move from theory to practice, can you share some examples of communities that are successfully implementing the "all sectors in" approach to address housing and community health? What can we learn from these models, and how might other communities replicate their success?

PD: I think Connecticut Children’s Building for Health truly epitomizes the “all sectors in” approach. What originally included detection and referral programs like Healthy Homes, the Energize CT weatherization programs, and employee assistance through Southside Institutions Neighborhood Alliance (SINA) has been expanded to include fuel assistance, housing code enforcement through the City of Hartford, and, interestingly, support for first-time pregnancies from the Nurse Family Partnership. All these different players, from diverse sectors, are collaborating to ensure connections between families and the resources they need.

MS: What is one common misconception or misunderstanding people have about the connection between housing and health, particularly when it comes to children’s well-being?

PD: One of the biggest misunderstandings is the failure to appreciate that interventions that strengthen families’ capacity to promote their children's optimal health development and well-being have extensive short and long-term return on investment. The notion is that [interventions in childhood are] expensive and it fail to produce ROI is wrong and we can even calculate the short and long term return on investment of funding interventions that strengthen families and communities to promote better outcomes for children and youth.

Despite the fact that we have the knowledge and even the capacity to do this, I don't think we have the will to do this. And I think is the one thing I would change if I could: I would give us the will to do things differently.

****

Marcus Smith is the Director of Research, Marketing, and Outreach at the Connecticut Housing Finance Authority (CHFA), where he helps drive statewide impact through data-informed strategies and compelling storytelling. With over two decades in mission-driven roles, Marcus has dedicated his career to expanding access to affordable, stable housing. His prior experience includes leadership in healthy housing initiatives at Connecticut Children's Medical Center and community development with Sheldon Oak Central. He holds a BA from the University of New Hampshire and an MBA from the University of Connecticut.