Housing and Mobility and Opportunity: An Interview with Cesar Aleman

Dec 16, 2024

In the second interview in our "Housing and..." series, we explore how trust, choice, and community-led action can reshape pathways to upward mobility.

CHFA presents the second installment of our interview series exploring the vital role housing plays across different facets of our communities. This series delves into how housing intersects with and influences sectors such as health, education, economic opportunity, and more. Each conversation features insights from thought leaders in their respective fields, highlighting the fundamental impact of housing on broader societal outcomes.

In this interview, we talk with Cesar Aleman, Director of CT Urban Opportunity Collaborative, a joint venture led by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, the Community Foundation for Greater New Haven and Fairfield County’s Community Foundation. Under Cesar’s leadership, the Collaborative is piloting a new initiative called the Changemaker Fund.

Cesar began his career as a property manager for a private real estate company in the Midwest. Since relocating to Connecticut, he has worked for various nonprofits that focus on areas such as fair housing, race and equity in education, and community organizing.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Marcus Smith: Reflecting on your personal and professional journey, what experiences or insights first drew you to work on mobility and opportunity, and how have those shaped your approach today?

Cesar Aleman: I think so much of my commitment to civil and human rights really has been rooted in my own experiences growing up. As an immigrant, my family's first “opportunity move” was bringing us to this country. And thinking about what that looks like for us to move out of a country that doesn't offer the type of educational opportunities that are necessary for children to break cycles of poverty. Growing up in California and having that personal experience of a completely unaffordable, unattainable housing environment was what I think catapulted my family into their own social economic mobility journey.

Those early experiences have been the pillars that lifted up my interest in doing this work-- without calling it racial equity work, without calling it justice work or mobility work. Terms like “mobility” or “opportunity’ are not the language that everyday people use. They’re not thinking of these highly academic conceptualized mobility frameworks for opportunity. People are just legitimately on a day-to-day thinking, “I want to get my family to a better place. This place is not working for us. We need to make different decisions, and we need to make moves.”

From my earliest days working in real estate, it became clear that housing is a pivotal system, a lens through which I can filter so much of my learning. I began to better understand the ways in which racism has created the kind of disinvestment that we see in housing and how crucial stable housing is to every social determinant of health. I began to recognize that, in the work that we do, what's really most critical is our ability to work with communities to build relationships and trust so that we can figure out how we can invest in people on their upward social economic journeys.

MS: What frameworks or guiding principles have shaped your approach to mobility and opportunity? Are there certain models or philosophies that you find particularly impactful, especially in relation to the resources people need to improve their life chances?

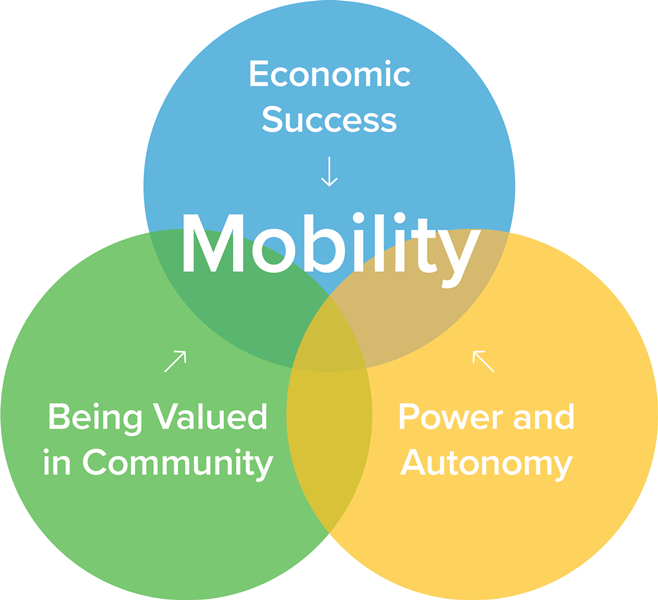

CA: The US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty is one that takes into account all of the pieces of mobility that feel really critical: economic success, power and autonomy, and being valued in community. Historically we have placed a high value on the economic success component of mobility-- moving people from lower earning wage jobs to higher earning wage jobs. Equally important to that, I think, is the power and autonomy that individuals and families can experience as they gain more resources and economic success. This framework allows us to think about how to support families on this journey, a journey where we're not just seeking the output of them having better resources or higher economic success, but instead taking into account that, along the way, families need to be valued in their community -- which means that they need to have power and autonomy so they can exercise better choices for themselves. And so, for example, moving a family out of a community where they are valued to a town with better schools but no grocery store that has access to the things that they like to eat – that can create a disruption in the opportunity journey that we're helping people to embark on.

Source: "Restoring the American Dream," Ellwood and Patel, 2018, a publication from The US Partnership on Mobility from Poverty

MS: It sounds like a more balanced approach is what is needed. That perhaps existing mobility and opportunity programs over-index on economic success, when what is needed is a consideration for all three components. What are the common pitfalls that existing programs fall into when trying to invest in this work?

CA: Programs often have very narrow goals that don't take into account the day-to-day challenges that a family experiences. We have excellent programs that support critical components of someone's existence, but the volatility of the market and the volatility that people experience daily requires a certain level of flexibility that you can’t get from, say, housing vouchers or Medicaid. These programs all serve an important purpose, but the reality is that people's lives change quite regularly. So today you might be short on rent, which a Section 8 voucher can help with. But tomorrow your priority is buying more food, and then the day after you might have to fix your car, and the next day you might have to get a babysitter…and you can't pay for those things with a Section 8 voucher.

MS: How does the Changemaker Fund aim to enhance mobility and opportunity in ways that may not be fully supported by these existing programs and structures? In what ways might it complement or expand upon those other programs focused on economic stability and empowerment?

CA: At its core, CT Urban Opportunity Collaborative is investing in people who are working together to create change.

So many of the problems that you and I have just described – housing insecurity, hunger, poor access to healthcare -- are problems that are experienced by hundreds of thousands of families and individuals across the state. Many people are trying to embark on a social economic journey to get to where they want to go. And yet, many of those same people are trying to figure out how to bring their communities along, too. This community component is really critical for the Changemaker Fund. We’re making a direct cash investment in resident leaders who are at the intersection of leadership, financial hardship, and systems change work.

Based on data from dozens of guaranteed income or direct cash programs across the country, a really good solution to people not having money is giving people money, and that in doing so you will see an increase of improved outcomes across the social determinants of health. We only launched a few months ago, but we're already seeing how this financial stability is impacting people’s social, emotional and mental state. People who had initially self-reported high levels of depression and anxiety now report being able to breathe a little easier and make different decisions and choices for themselves because they have more stability. And that’s a beautiful thing to see.

MS: For those practitioners who want to get started, what is a good first step in improving mobility and opportunity-related outcomes for the folks they serve?

CA: The number one guiding principle is to invest time, early on, in listening to the community you seek to serve and build relationships. It’s an investment that yields trust and can help you identify shared approaches to resolve whatever issues you’re working on. Connected to that is an investment of real resources that needs to come in the form of dollars. Take for example someone enrolled in a workforce development certification class that will help them move out of a low-wage job. They may be doing great for three weeks, but then their car breaks down. They put money into fixing their car, but then they’re short on rent. Now they need to pick up a second shift so they can make rent, which means they’re missing a certification class. These day-to-day pressures snowball, but an investment in real resources – in addition to the certification class – could give people the flexibility they need to get to where they want to go.

Regardless of what system you work in – whether it’s housing or healthcare or workforce development -- think of it as building a culture where we invest in people’s hopes and dreams. That investment comes in the form of time, in the form of resources, and in the form of trust.

MS: If you could change one thing to make mobility and opportunity more accessible, what would it be? How do you think this change could transform people’s capacity to reach their potential?

CA: One of the biggest challenges we have right now, not just in Connecticut but across the country, is that we have built up all of these institutions and systems that really disincentivize families from doing better. Many of these rigid public benefit programs penalize people when they're on a trajectory to mobilize their finances and their resources on this journey towards economic success.

For somebody earning minimum wage, making $1.50 an hour more can put their paycheck just over the limit for whatever benefits they're receiving. And as a result, they began to lose benefits. These “benefit cliffs” are creating barriers for families that are right at the cusp of attainment. If we were better able to understand how to remove some of those systemic barriers by creating different policies and practices that really allow families to feel incentivized and invested in, I think that we would see improvements across various sectors.

As practitioners, we need to ask ourselves, “How do we do work that honors people's dignity, elevates people's opportunity and attainment, and creates vibrant environments and cultures where people can thrive and experience joy and happiness?”

****

Marcus Smith is the Director of Research, Marketing, and Outreach at the Connecticut Housing Finance Authority (CHFA), where he helps drive statewide impact through data-informed strategies and compelling storytelling. With over two decades in mission-driven roles, Marcus has dedicated his career to expanding access to affordable, stable housing. His prior experience includes leadership in healthy housing initiatives at Connecticut Children's Medical Center and community development with Sheldon Oak Central. He holds a BA from the University of New Hampshire and an MBA from the University of Connecticut.